CTE Matters To Me

- …

CTE Matters To Me

- …

CTE Matters to Me

Welcome. Our mission is to:

- raise awareness of CTE - chronic traumatic encephalopathy - especially in New Zealand

- raise awareness of the devastating and tragic consequences of misdiagnosing brain injury as a 'mental health' or 'psychiatric' issue

- raise awareness of the need for medical education & training which includes the identification of brain injury and possible CTE

- collate links to information about treatment for people who have possible/probable CTE

- provide mutual support, understanding and networking among people and families of those who have probable CTE

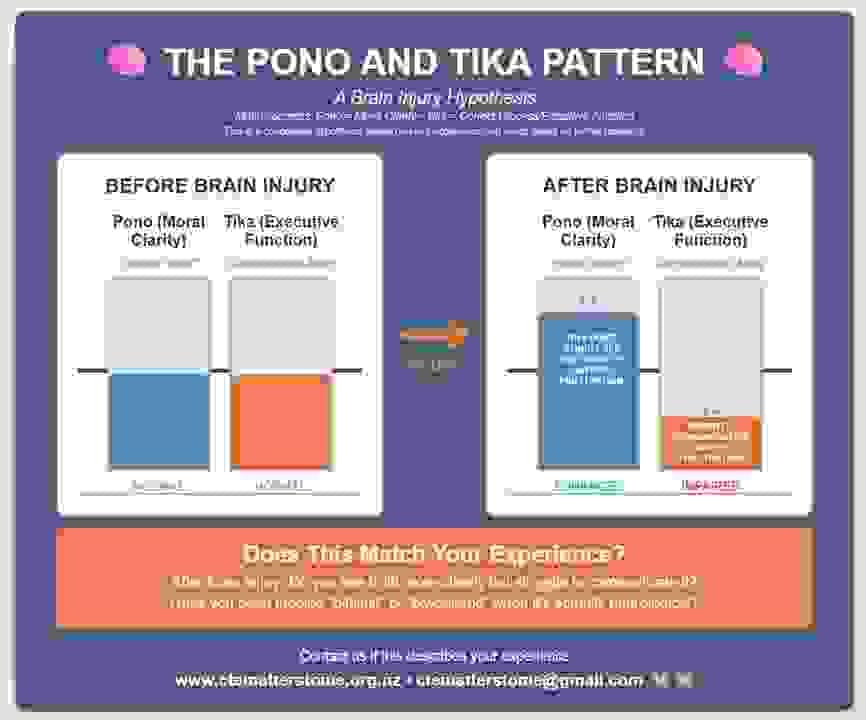

- present our hypothesis of 'The Pono and Tika Pattern' as distinct symptoms and markers of CTE, and invite feedback

- develop a standard of care for people who have probable CTE

What is CTE?

- Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy is a progressive neurodegenerative disease.

- Caused by repetitive head impacts over time (not single incidents).

- Cannot be definitively diagnosed while living, but symptoms can be recognized.

- Symptoms typically appear 8-10 years after head impact exposure.

CTE Risk Factors:

- Contact sports (rugby, boxing, football, hockey)

- Military service with blast exposure

- History of domestic violence

- Multiple concussions or subconcussive impacts

- Any pattern of repetitive head trauma

CTE Treatment:

CTE needs treatment for brain injury, not for a 'mental health condition' or a 'psychiatric condition'.

Please see the section 'CTE Treatment' for information about treatment.

CTE Education:

Consider a curriculum of medical education and training which doesn't include:

- a strict adherence to the first principles of medicine — "First, do no harm" (primum non nocere), reflected in the Medical Council of New Zealand's foundational standard: "Make the care of patients your first concern" (Good Medical Practice, November 2021)

- foundational knowledge of brain injury

- recognising brain injury

- discerning brain injury from 'mental health conditions' and 'psychiatric conditions'

What would be the possible consequences?

We Remember

The late Shane Christie, New Zealand Rugby Player and truthseeker, with suspected CTE

The late Billy Guyton, New Zealand Rugby player with confirmed CTE

Introduction

Chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE)

Why I stopped watching football

The devastating consequences of misdiagnosis

Put yourself in the shoes of someone who has had repeated head knocks through sport and knows their difficulties are due to those injuries. They seek help, but doctors dismiss their head trauma history and instead diagnose them with a "mental health" condition like 'bipolar disorder'.

This happens far too often. People with probable CTE face a medical system that doesn't understand brain injury symptoms and defaults to psychiatric diagnoses instead.

"The worst thing about probable CTE to me is not the disease, it's not being believed." - Ange Murtha

If this sounds like your experience, you're not alone. There are medical differences between CTE and psychiatric conditions, and you deserve proper evaluation, and [roper treatment.

Treatment for CTE

New!

Mental Health Changes from Brain Injury & the Use of Photobiomodulation to Improve Quality of Life

He Couldn’t Think Clearly for Years — Until This Red Light Fixed His Brain (CTE)New!

A New Avenue for Lithium: Intervention in Traumatic Brain Injury

Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy: Update on Current Clinical Diagnosis and Management

Recent Preclinical Insights Into the Treatment of Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy

Lithium treatment for chronic traumatic encephalopathy: A proposal

Recent Preclinical Insights Into the Treatment of Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy

Lithium: A Novel Therapeutic Drug for Traumatic Brain Injury

A New Avenue for Lithium: Intervention in Traumatic Brain Injury

VA research on Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI)

Best Nootropics for Traumatic Brain Injury

Personal Stories from The Concussion FoundationShine a Light on CTE — Help Prove There's Hope

Help Ange Heal — and Prove It's Possible for Others

Ange is an all-round sportswoman from Hokitika on the West Coast. Like so many Kiwis, she grew up living the active outdoor life — rugby, skiing, snowboarding, mountain biking. She'd completed a horticulture diploma and was building a new career when, in 2011, after years of repeated head knocks since childhood, she had her first seizure just eight days after her last rugby game of the season.

Instead of being treated for brain injury, Ange was misdiagnosed with a psychiatric condition. She was later forcibly detained in a psychiatric unit and drugged for something she does not have.

For fourteen years, Ange kept saying: "This is from the head knocks. I have a brain injury."

To this day, Ange has never received proper treatment for her brain injury. The last care she had was from a concussion team in 2016 — before the system shut her out.

But Ange hasn't given up.

Even while experiencing progressive decline, she has connected with the international CTE community and found purpose in helping others facing the same fight. Through 'CTE Matters To Me', Ange and Elisabeth are working to raise awareness, challenge the systems that failed her, and support others affected by brain injury.

Now Ange wants to heal — not a miracle cure, but real, tangible improvement. And she wants to prove it's possible for others too.

What is a Vielight?

The Vielight Neuro Gamma 4 is the world's most researched brain photobiomodulation device. It delivers near-infrared light through the skull and nasal passage to reach deep brain structures, stimulating mitochondria at a cellular level to help damaged brain cells heal. It's backed by over 35 published clinical trials across conditions including traumatic brain injury, Alzheimer's, and cognitive decline.

This isn't experimental wishful thinking — it's cutting-edge neuroscience, and it could be a game-changer for Ange.

How You Can Help

We're raising NZ$3,700 to cover the cost of the device, international shipping, customs duties, and platform fees.

Every dollar brings Ange closer to healing — and helps prove that hope is real for everyone living with brain injury.

As Ange says: "The only way through is together."

👉 Donate now: https://givealittle.co.nz/cause/shine-a-light-on-cte-help-prove-theres-hope

The Pono and Tika pattern

In our conversations about brain injury and CTE, Ange and I have noticed a common pattern, which is that people with brain injuries often experience two things at once:

1. enhanced moral clarity- i.e. seeing the truth and wondering why others can't see it too, which leads to intense frustration, and

2. impaired and inhibited communication, which also leads to intense frustration.

It seems to us that this combination of experiences leads to anger and grief (which is not the same as 'depression'). These issues are neurological, not psychological or 'psychiatric'.

Does this match your experience? If so, we'd love to hear from you.

Contact

Please feel free to send us an email or phone us. Thankyou